It’s the Holiday Season!

UPark is offering several chances for Christmas worship

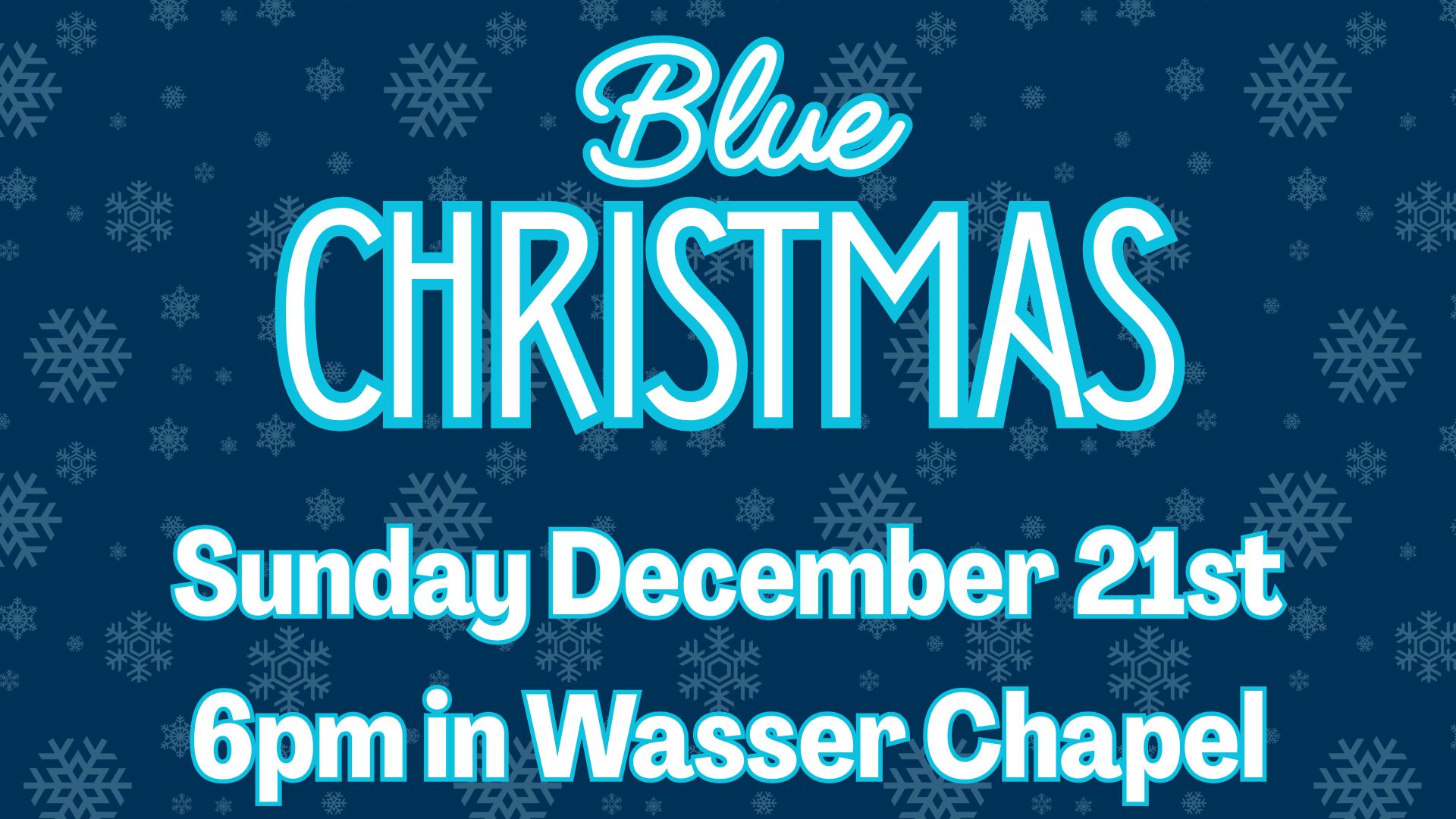

BLUE CHRISTMAS

Sunday, December 21st @ 6PM in Wasser Chapel

This will be a more contemplative and introspective service designed for those who are struggling with grief during the holiday season.

JINGLE JAM: Wednesday, December 24th @ 4PM in Sanctuary

This will be a family-friendly, song-filled experience designed for kids and adults to share in the joy of Christmas.

TRADITIONAL: Wednesday, December 24th @ 7PM in Sanctuary

This is our traditional and more formal Christmas Eve service. There will be candlelight and our Chancel Choir will perform.

CONTEMPLATIVE: Wednesday, December 24th @ 11PM in Wasser Chapel

This is a much more contemplative and calm Christmas Eve service. There will be candlelight and Communion.